Aspartame is one of the most common sugar substitutes, turning up in everyday items like chewing gum, soft drinks, and tabletop sweeteners. It is popular because it delivers sweetness with far fewer calories than regular sugar, so it often shows up in “light” or “zero” products. But fresh research is raising new questions about what long term, low level intake might be doing inside the body. The latest findings point to possible effects on both heart performance and the way the brain uses fuel.

In the new experiment, scientists in Spain tracked what happened when mice were given small doses of aspartame over an extended period. The mice did not receive it constantly, but in repeated stretches over the course of a full year. The amount they consumed was described as roughly one sixth of the daily intake the World Health Organization considers safe for people. That detail matters because the study was designed to mirror realistic exposure rather than extreme dosing.

One result looked appealing on the surface. The mice consuming aspartame lost more weight than the mice that did not, and by the end they carried about 10 to 20 percent less body fat. For anyone who has swapped sugar for sweeteners to manage weight, that sounds like a win. The catch was that the same mice also showed signals that hinted at possible trouble in major organs. In other words, the scale moved in one direction while other measurements raised eyebrows.

When researchers examined the animals’ hearts, they found signs the heart was not working as efficiently. The hearts did not pump blood as effectively as the comparison group, and the team also noted small structural changes. Those shifts suggested extra strain on the cardiovascular system even at relatively low intake levels. While animal findings do not automatically translate to people, the pattern is enough to push the conversation beyond calories alone.

The brain findings were just as interesting, and arguably more unsettling. The study tracked changes in how the brain used glucose, which is a key energy source for brain activity. Early on, glucose consumption went up, but by the end it dropped sharply, which could have negative implications for brain function. The mice also performed worse on memory and learning tasks, moving more slowly and taking longer to solve a maze, which suggested a mild decline in cognitive performance.

The researchers did not frame the results as a final verdict, but they did urge caution for younger age groups. They wrote, “Until the neurological effects of aspartame are better clarified, children and adolescents should avoid it as much as possible, especially as a regular part of the diet.” That is a strong statement, and it reflects how seriously scientists take even mild shifts when they involve developing brains. It is also a reminder that the “safe for most adults” conversation can look very different when kids and teens are involved.

The mouse study also sits alongside evidence from human research that points in a similar direction. A separate study published in September followed nearly 13,000 people and linked aspartame and other artificial sweeteners to weaker cognitive abilities, with the association especially noticeable among people with diabetes. That does not prove causation, but it strengthens the case for looking closely at how these sweeteners interact with metabolism and brain health over time. Taken together, the animal and human findings lean toward a cautious interpretation rather than a shrug.

The authors of the latest work also emphasized that the brain changes they observed were relatively mild compared with earlier studies that used more intense exposure. Even so, they argued the results should not be ignored, because the doses were not extreme and the timeline was long. They concluded, “These findings suggest that aspartame, even at permitted doses, can impair the function of important organs, and it would be advisable to reconsider the safety limits for human use.” That is not a call for panic, but it is a call for better answers, especially about long term intake.

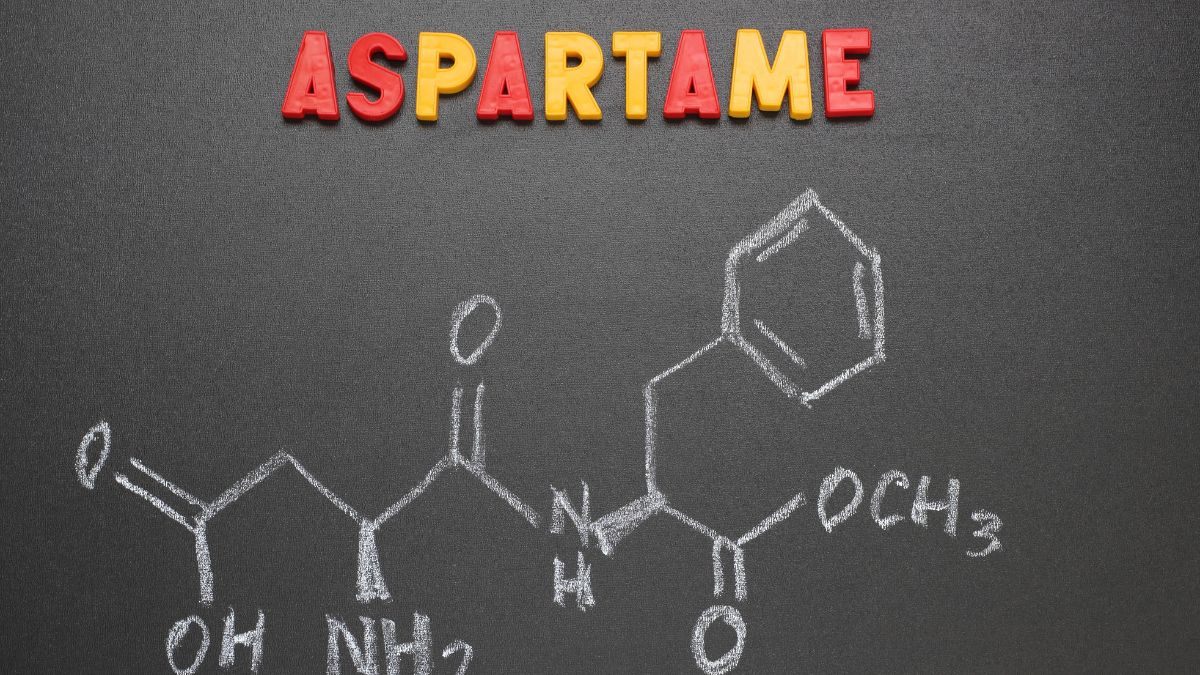

For readers trying to put this into context, it helps to understand what aspartame is and why it is everywhere. Aspartame is a low calorie sweetener made from two amino acids, which are basic building blocks of proteins. It is far sweeter than table sugar, so manufacturers can use tiny amounts to achieve a similar taste. That is why it shows up in products meant to reduce calories, including diet beverages and sugar free sweets, and it can also appear in some medications and supplements.

It also helps to separate the idea of hazard from real world risk, which often depends on dose and frequency. Health agencies set acceptable daily intake limits to reflect an amount considered safe over a lifetime, and those limits are meant to build in a cushion for typical consumers. Real life intake varies a lot, though, especially for people who drink multiple diet beverages a day or rely on sweetened products as a routine habit. There is also one group that is generally advised to avoid aspartame entirely, people with phenylketonuria, because they must limit phenylalanine.

If you use aspartame regularly, the practical takeaway is not necessarily to eliminate it overnight, but to treat it as something worth paying attention to rather than a free pass. Rotating sweetness sources, reducing dependence on ultra sweet flavors, and keeping an eye on overall dietary patterns can help lower long term exposure without making life miserable. And if you are choosing products for kids or teens, the caution flagged by the researchers may be worth taking seriously. What do you think these findings should mean for everyday diet choices and product labeling, share your thoughts in the comments.